Kelanmee Shetland Sheepdogs

Where quality and conformation is everything

The Shetland Sheepdog

Illustrated Standard

(AUSTRALIAN BREED STANDARD EXTENSION)

GENERAL APPEARANCE CHARACTERISTICS TEMPERAMENT HEAD AND SKULL MOUTH EYES

EARS NECK FOREQUARTERS BODY HINDQUARTERS FEET TAIL GAIT/MOVEMENT

COAT COLOUR HISTORY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NECK

Muscular, well-arched, of sufficient length to carry the head proudly.

Although quite adequately described, this feature needs special emphasis because it is currently too seldom seen. This is a great pity as besides contributing to the flowing outline and proud head carriage, a reachy, crested neck adds so greatly to the look of distinction which a really top-class Sheltie should possess. It is also important because in a breed of normal construction such as this, adequate length of neck will generally accompany adequate length of body and reasonable shoulder angulation. Without all these features, a Shetland is unlikely to he able to stride out with the necessary freedom.

Conversely, the short, thick neck, frequently combined with steep shoulders and insufficient length of body, gives a dumpy outline and restricted movement, neither of which can he described as graceful.

It must be remembered that the full adult coat (more especially the mane of the male) tends to disguise the reach of neck, so a "stuffy" necked puppy is most unlikely to grow into an adult with proud and impressive head carriage.

FOREQUARTERS

Shoulders very well laid back. At the withers separated only by vertebrae, but blades sloping outwards to accommodate desired spring of ribs. Shoulder joint well angled. Upper arm and shoulder blade approximately equal in length. Elbow equidistant from ground and withers. Forelegs straight when viewed from front, muscular and clean with strong, but not heavy bone. Pasterns strong and flexible.

Some people profess to find shoulders difficult to assess which is presumably the reason that the upright shoulder is a common and persistent fault, In fact the good shoulder is not difficult to recognise and should be apparent without the need to handle the dog. The poor shoulder is even easier to recognise as it is likely to produce glaringly obvious faults in both stance and movement.

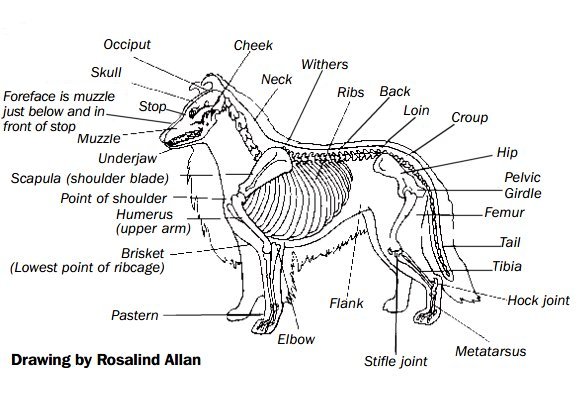

The well-laid-back shoulder (scapula) descends diagonally from well-defined withers to meet the upper-arm (humerus) at what is generally called the "point of shoulder". The upper-arm should then run back at an angle of about 90 degrees from the shoulder to the elbow, the elbow, it will be remembered, should be equidistant from both the withers and the ground. If all the lengths and angles are correct, the elbow will be placed approximately beneath well set back withers. The dog will then be standing with its legs well under it, with a well-developed forechest.

If the shoulder and/or upper-arm are too steep, the withers will be scarcely discernible as the upper tip of the scapula will he obscured by the base of the neck.

The legs may appear to be in a perpendicular line down from the ears to the ground and there will be no apparent forechest because the sternum (breastbone) will be obscured by the upper-arm. The stride will be short and choppy and the forelegs may well be lifted too high. In fact the dog will look quite unbalanced in both stance and movement.

Now for the stipulation that the upper-arm and shoulder blade should be approximately equal in length. The short upper-arm is one of the faults most frequently criticised, but it may not be quite as common as suggested, if only because the term "point of shoulder" is highly ambiguous. The shoulder-assembly is really the combination of the shoulder blade (scapula) and upper-arm (humerus), which meet in a ball-andsocket joint.

Angulation

The tip of the humerus, and then continues slightly to enclose and protrude slightly beyond the end of the scapula. So it is the upper-arm, not the shoulder-blade which should be measured from this point. The end of the shoulder-blade lies fractionally farther back.

The foreleg is required to have "strong" bone. This does not mean "heavy" bone. The heavily-boned foreleg will seldom accompany a flexible pastern but it will all too frequently run straight down, with a "thick ankle" instead of a flexible pastern, to a clumsy round foot. The flexible pastern is vital as a shock absorber, but it must not be so sloping as to indicate weakness.

BODY

Slightly longer from point of shoulder to bottom of croup than height at withers. Chest deep, reaching to point of elbow. Ribs well sprung, tapering at lower half to allow free play of forelegs and shoulders. Back level, with graceful sweep over loins; croup slopes gradually to rear.

This description of the length of body corrects an error in the previous Standard and should be noted carefully. The measurement now given provides for a body of medium length. It should not be too long in the back (i.e. from the withers to the hips), as this would suggest a weak spine. The length that gives strength is that measured from the point of really well-angulated shoulders to the lowest point of a correctly sloping croup. This construction allows scope for powerful hindquarters to achieve maximum propulsion and to combine with well-angulated forequarters to provide the desired length of stride. A too short body inhibits freedom of movement and the flexibility required for turning at speed.

The depth of chest is often flattered by a profuse coat and should be checked by touch when judging. The well-sprung but tapering ribs are very important. Barrel ribs (or, for that matter, obesity) can force the shoulders and elbows out of alignment and so distort the movement as well as making the dog look dumpy. On the other hand "slab sides" (narrow flat ribs) may be associated with tied elbows and mincing movement as well as causing a narrow chest with consequent lack of heart-and-lungroom.

The level back (i.e. without dippiness) flowing into the graceful sweep over the loins should not suggest a hint of roach, being simply the fact that the Sheltie, as a galloping breed, should have strong, very slightly arched loins, the "graceful sweep" being enhanced by the gradually sloping croup and low-set tail.

HINDQUARTERS

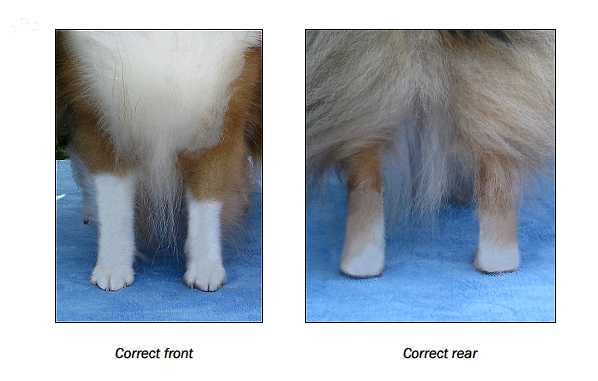

Thigh broad and muscular, thigh bones set into pelvis at right angles. Stifle joint has distinct angle, hock joint clean cut, angular, well let down with strong bone. Hock straight when viewed from behind.

The description of muscular, well-angulated hindquarters sweeping down to lowset, well-angled hocks suggest yet again the construction necessary to provide powerful, flexible propulsion at any speed. As with the steep shoulder or too short upper-arm, lack of angulation or of adequate length of any of the bones of the hindquarters will give a short, stilted stride with too much up-and-down motion. To achieve rhythmic movement it is obvious that the construction of the fore- and hindquarters must balance one another perfectly. The ideally angulated forehand cannot function correctly without the cooperation of equally well-angulated hindquarters and vice versa. Obviously the bone structure cannot function adequately without the help of well-exercised, normally developed muscles. On the other hand, muscles, which are grossly overdeveloped in some specific area, may be compensating for a fault of construction or an injury.

FEET

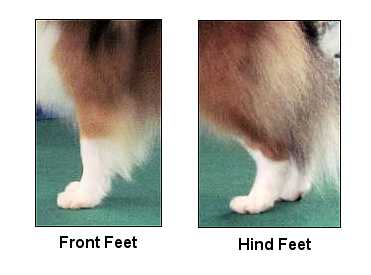

This is the ideal foot for the small, active dog required to move at speed on rough, rocky or slippery ground. The big, round foot (likely to accompany heavy bone) or thin, flat, splayed foot (usually seen with thin, weak and spindly bone, sometimes the result of generations of poor rearing) are much less efficient as well as aesthetically unpleasing. Like the flexible pasterns, thick -pads act as shock absorbers as well as protection, while strong, well-arched toes give grip when changing speed or direction.

TAIL

Set low; tapering bone reaches to at least hocks, with abundant hair and slight upward sweep. May be slightly raised when moving but never over level of back. Never kinked.

This is self-explanatory. A continuation of the spine, the long, gracefully carried tail completes the beautiful flowing outline.

The upward sweep (neither an acute twist nor a hook) may only be noticeable in movement. In the case of a too-short tail it may not be apparent even then, but the inert tail that hangs absolutely lifelessly even when the dog is moving at speed is likely to have been injured or otherwise damaged.

The maximum height to which the tail may be raised when moving is a line, which continues that of the back.

When checking the tail for length, it should also he examined carefully in case it is kinked. Kinks are misplaced (sometimes accidentally displaced) vertebrae. Kinks can be situated anywhere along the tail, from the root to the tip. Occasionally puppies may be born with very short tails which are kinked in several places, this is not only most unsightly, but can also present practical problems. So kinked tails should be avoided at all costs.

Page 3

Contact Details

Kim at Kelanmee SheltiesSouthern Highlands, NSW, Australia

Email : [email protected]